Engage with Health Authorities to Mitigate & Prevent Drug Shortages

When faced with large-scale disruptive events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the emergency and business continuity plans of drug manufacturers and event-specific actions of health authorities may not always be sufficient to prevent shortages of critical medical products. However, early, transparent engagement with health authorities is a powerful opportunity for drug manufacturers to potentially mitigate or avoid drug shortages. This article offers an overview of the pathways for a drug manufacturer to notify and collaborate with health authorities to minimize the impact of a drug shortages, whether or not there is an ongoing pandemic or large-scale disruptive event.

With the early public reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic resulting in bare shelves at grocery stores, it has become easier for all of us to understand the struggle healthcare providers experience when they cannot obtain critical medical products. Drug shortages can have significant impacts on patients and the healthcare system, including delays or rationing of care, difficulties finding alternative drugs, increased risk of medication errors, higher costs, reduced time for patient care, and hoarding or stockpiling of drugs that are in shortage.1Depending on the length of the shortage, providers may have to cancel or delay procedures or patients may go without medicine, leading to significant, detrimental effects on patients and public health.

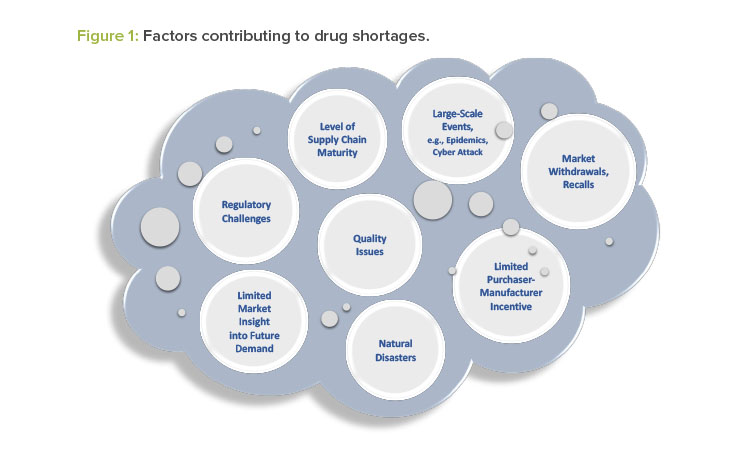

Drug manufacturers typically have emergency and business continuity plans to ensure the continued supply of critical medical products. Nevertheless, an actual or potential drug shortage may occur for a variety of reasons, some of which are unexpected and not within the control of the drug manufacturer. Figure 1 illustrates several factors that contribute to drug shortages.

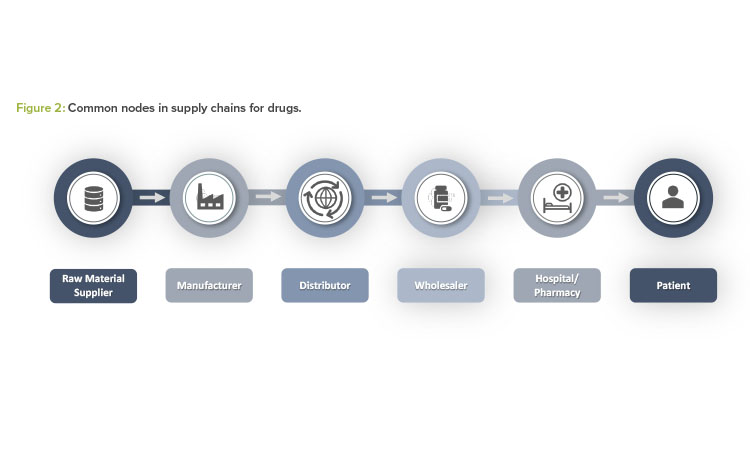

Drug shortages may result from issues occurring at any node within the overall supply chain of a drug product. Figure 2 provides a high-level snapshot of common nodes within a supply chain for a pharmaceutical product.

Over the course of the past several years, many health authorities have developed sophisticated tools and practices to address actual and potential drug shortages. Each of these tools relies on drug manufacturers having full and transparent communication with the relevant health authority as early as possible to obtain timely, tailored support to mitigate a drug shortage. Janet Woodcock, MD, Director of the US FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), described the FDA’s proactive approach toward shortages as follows:

We have the most success in all of this by working closely with manufacturers to help prevent shortages actually before they occur. This means we need to know about potential supply disruption before it happens, not when hospitals start calling us.2

Additionally, health authorities may find it necessary to quickly modify or enhance regulations and pathways in response to large-scale events that significantly affect the overall supply chain. For example, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the US CARES Act, which became law in March 2020, expands requirements for notification of drug shortages, with new requirements to report on (a) shortages for any drug that is critical during a public health emergency, and (b) shortages or discontinuations of an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API).3. Similarly, the European Commission and the European Medicines Regulatory Network created a task force and published guidance on adaptations to the regulatory framework to address challenges arising from the COVID-19 pandemic.4, 5

Drug Shortage Notifications

Once the potential for a drug shortage has been confirmed, drug manufacturers may be required to take expedient action to notify the health authority and implement mitigation actions to maintain continued supply. In many markets, regulations mandate that manufacturers report specific elements as part of the health authority notification of an actual or potential drug shortage.

Depending on the situation, drug manufacturers may also choose to include additional information in drug shortage reports. The aim should be to provide information that allows the health authority to support the manufacturer and reduce the duration of shortages, find alternative solutions to make treatments available to patients, or prevent some shortages altogether.

When engaging with a health authority, it is important for a drug manufacturer to be prepared to discuss the following information, as applicable:

- A summary of the reason for the actual or potential shortage

- A full description of the product(s) involved, including the name, dose, strength, packaging configuration, and any tracking or tracing information, such as the stock keeping unit (SKU) and National Drug Code (NDC) numbers

- The approved indications for use of the product, including nonapproved uses that are established or known in the medical community

- A general description of the supply chain

- A timeline of when the shortage is expected to occur, how long it will last, and when all existing product will be exhausted

- A description of the level of inventory that may be impacted, and the estimated volume of historic monthly sales, usage, or demand, as applicable

- A description of estimated market share for the product and whether the entire market share may be affected by the issue creating the shortage

- A description of what the drug manufacturer is currently doing to mitigate the shortage and resupply the market

- Ideas about how the health authority may assist in addressing a drug shortage, where and when appropriate

- A communication plan for informing healthcare providers, pharmacies, distributors, patients, or other health authorities, if needed

- A draft of any external notification of the shortage to the general public, if needed

If some of the drug shortage information described here is not yet available early in an event, drug manufacturers should notify the relevant health authorities with the information that is available and provide subsequent updates as the details emerge. Additionally, manufacturers should share other important information with the health authorities to assist with evaluating appropriate mitigation strategies, such as information on whether there are generic or alternative treatments available for each indication, and potential product surpluses in other markets.

Other products, such as APIs, personal protective equipment, medical devices, and diagnostics have historically not been subject to requirements for health authority notification. However, regulations are evolving rapidly; some jurisdictions now require reporting shortages for these product types during a public health emergency such as the COVID-19 pandemic or require this expanded reporting at any time. Even when notification is not required, health authorities are open to receiving notification of actual or potential shortages of all products and are willing to provide support and guidance to mitigate any critical impacts on patients and the public health.

An example of market-specific guidance on health authority notification may be found in the FDA-issued guidance, “Notifying FDA of a Permanent Discontinuance or Interruption in Manufacturing Under Section 506C of the FD&C Act,” which was implemented as part of the agency’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.6 The guidance provides information regarding the “who, what, when, where, and how” of notifying the FDA of actual or potential shortages and, importantly, expands the reporting obligations to include products that may be needed in response to COVID-19. This document is applicable for the duration of the COVID-19 public health emergency, and it will be important to watch for any revisions or replacements of this guidance that may occur after the public health emergency has concluded.

Health Authority Tools and Practices

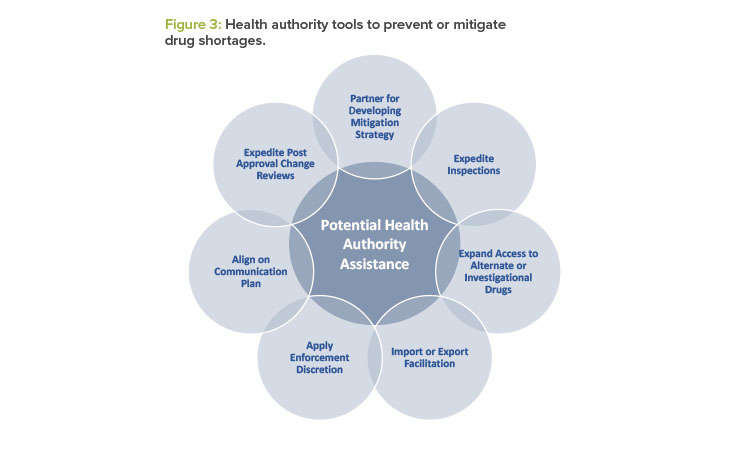

After a health authority has received the manufacturer’s initial notification, the health authority may partner with the manufacturer to prevent or mitigate a drug shortage. Depending on the medical necessity of the drug, the availability of generic or alternate therapies, and the root cause of the actual or potential drug shortage, health authorities may use several tools to tailor their response to the underlying root cause. See Figure 3 for examples of actions health authorities may take.7

Enforcement discretion is one of the most impactful, yet often misunderstood, tools that a health authority has to address drug shortages. The term “enforcement discretion” pertains to the ability of a health authority to determine whether to enforce select regulatory provisions as they currently apply to certain manufacturing entities or activities. Health authorities exercise enforcement discretion on a temporary basis when other tools or practices are insufficient to mitigate or prevent the shortage of a medically necessary drug. It is important to note that this tool is only used when (a) the patient benefit or necessity outweighs the potential risks associated with exercising the enforcement discretion, and (b) the proposed temporary solution is timely enough to mitigate or prevent a shortage.

For example, health authorities may use enforcement discretion or regulatory flexibility to develop risk mitigation measures to allow individual batches of a drug product to be released even when quality assurance requirements or the registered dossier requirements have not been met. Historical examples of enforcement discretion include:

- Allowing additional product testing prior to release

- Extending the expiry of select product batches on the market

- Temporarily allowing distribution of products with outdated or modified labeling and packaging

- Supplementing product distribution with accessories such as filter needles or other administration components to remove particulate matter

In the specific case of expiry dating, manufacturers may also consider submitting a postapproval change to extend expiry for all future manufacturing batches to alleviate shortage events. Depending on the scenario, the health authority may support expediting a submission of this nature to minimize the current shortage event or to prevent future shortages.

Manufacturers are encouraged to engage in an open dialogue with the health authority regarding all potential options to mitigate the shortage. As a part of the dialogue, manufacturers should collaborate with the health authority and identify any potential assistance that the health authority can provide (see Figure 3).

Communication with Stakeholders

When a drug shortage occurs, timely and effective communication is an important tool to ensure that all stakeholders are aware of the current drug supply status and remediation efforts in place to address the shortage. Both drug manufacturers and health authorities may wish to communicate regularly with customers (e.g., healthcare providers, wholesalers, distributors, hospitals, pharmacies, patients), and other stakeholders (e.g., professional organizations, the general public) until the shortage has been resolved.8

The drug manufacturer should notify the relevant health authority before any necessary public communications are released. This approach helps ensure that the health authority and manufacturer can coordinate actions to prevent or mitigate a drug shortage and to make consistent information for customers available. In some cases, a drug manufacturer may be able to coordinate with the health authority to redirect patients or purchasers to locations where adequate supplies of the drug product are available.

Any external communication to the general public issued by a drug manufacturer about an actual or potential drug shortage may need to be reviewed by the health authority prior to distribution. In Europe, EMA guidance includes a template for such communications, which has also been translated into multiple local languages by National Competent Authorities.9, 10 Some health authorities, such as the US FDA and EMA, may also recommend or require that drug manufacturers obtain health authority review of specific communications to healthcare providers about a drug shortage (i.e., a “Dear Healthcare Provider” letter).

Some drug manufacturers may be wary about reporting actual or potential drug shortages to health authorities because they are concerned that the health authority will share the information publicly without working with them. This hesitancy may result in delayed health authority notifications, which in turn could affect the ability of the drug manufacturer to partner with the health authority to mitigate an impending shortage. Based on experience to date, drug shortage information provided by a manufacturer to a health authority is not automatically communicated publicly without prior discussion with the drug manufacturer. Additionally, health authorities typically only communicate shortage risks publicly when there is a need for the end users or prescribers to do something differently to manage the shortage situation. Thus, it is in the best interest of drug manufacturers to communicate as early as possible with health authorities to allow more time to mitigate shortages and decrease the likelihood that an external communication is needed.

If a drug manufacturer decides that they would like to communicate externally, they may wish to coordinate with the relevant health authority to publish the information on the health authority website at the same time that it is made available through other communication channels. Health authorities may maintain websites (e.g., www.hma.eu/598.html) and mobile apps that list of ongoing drug shortages to facilitate the availability of accurate and reliable information for healthcare providers and patients. In some cases, manufacturers are able to use these tools to provide information about where their drug product can be obtained or list contact information to provide additional support to patients or healthcare providers.

Closure of Drug Shortage Communications

After initiating communications with the relevant health authority, drug manufacturers should continue to track the progress of the event closely, up-date the health authority as needed, and ensure external communications and websites remain current. An ongoing update process is generally expected until the supply disruption is resolved and a closure communication is made to the health authority, customers, and other stakeholders.

Furthermore, once normal inventory has been achieved and all back orders for the product addressed, the drug manufacturer should evaluate the event and take any appropriate measures to prevent future shortages, including follow-up with relevant health authorities, if appropriate. Per the ISPE Drug Shortages Plan, lessons learned from the event should be used to improve product design, quality systems, and facilities so as to prevent future drug shortages.11

Manufacturers may need to share their findings from the evaluation and their plans for preventive actions with the health authority. Companies should also use this information to improve business continuity plans, employee practices, and drug shortage processes and procedures.

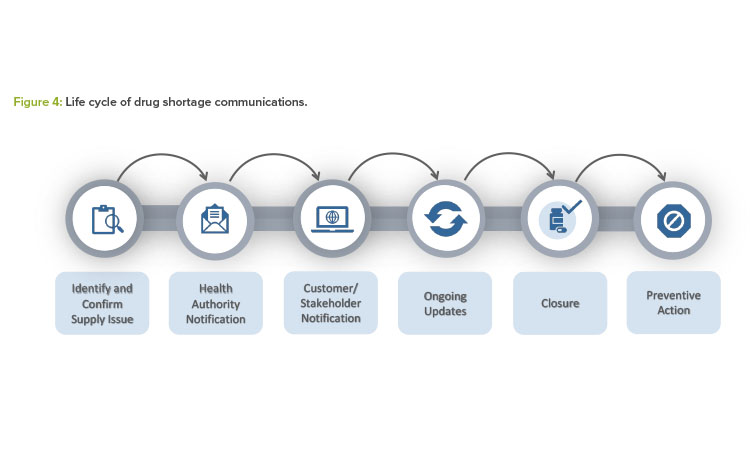

Figure 4 summarizes all the steps described in this article for effective health authority communication and mitigation or prevention outcomes.

Case Study

In September 2017, Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico, creating a shortage in the United States of a significant number of critical medical products manufactured on the island, including human drugs and components. In particular, normal saline and sterile water for injection were subject to extend-ed shortages that lasted several months. These shortages affected hospitalized patients who needed life-saving medicines that rely on normal saline or sterile water for injection as a solvent or diluent vehicle for parenteral administration.

To mitigate the public health impact of the shortages, the FDA worked with drug manufacturers to approve new facilities and temporarily import product from other countries. The FDA also used data provided by drug manufacturers to extend expiry dates and issued guidance to provide alternate treatment and conservation strategies.12 By increasing supply, managing existing inventory, and communicating frequently with the public, the FDA was able to partner with drug manufacturers to protect the public health and to provide a timely and impactful response to Hurricane Maria.

Additionally, the impact of Hurricane Maria and other recent large-scale events inspired active global dialogue on the topic of drug shortages. This dialogue has become heightened during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has had a worldwide impact on all types of medical products, including human drugs, medical devices, personal protective equipment, biologics and blood supply, nutritional products, and animal drugs. The discussion is putting a spotlight on systemic vulnerabilities associated with drug supply and how health authorities and industry may better prepare for continuous supply of critical medicines for patients. ISPE encourages all manufacturers to stay current with the developing initiatives and potential for new regulations related to drug shortages.

Conclusion

Full and transparent communication with the relevant health authority is essential to obtain timely, tailored support to mitigate a drug shortage. The earlier a drug shortage can be identified, confirmed, and reported, the more likely the health authority can assist in providing expedited action to prevent the shortage and maintain continued supply. With robust business continuity planning and effective communication practices, drug manufacturers will be in the best position to collaborate with health authorities and minimize the impact of an actual or potential drug shortage on patients and the public health.

ISPE has had a longstanding commitment to preventing and mitigating drug shortages. For more information on successful interactions with health authorities, as well as in-depth information regarding other significant dimensions for preventing drug shortages, we refer you to the ISPE Drug Shortages Prevention Plan11 and Drug Shortage Assessment and Prevention Tool13 as key resources.

The ISPE Drug Shortage team is actively monitoring developments with drug shortages and is available for any related questions. We welcome input on best practices to support continuity of supply and decision making in the case of an actual or potential drug shortage.

About the Authors

Acknowledgements

ISPE Drug Shortage Initiative Team

The Drug Shortage Initiative Team contributed to this article. Team members are:

BRAND COMPANIES: Diane Hustead (Merck) – Chair; Nasir Egal (Sanofi); Karen Hirshfield (J&J); Nick Melone (BMS); Deborah Tolomeo (Genentech)

GENERIC COMPANIES: Dawn Culp (Mylan); Donna Gulbinski (Civica Rx); Emma Harrington (Novartis/Sandoz)

INDUSTRY ASSOCIATES: Melissa Figgins (Coal Creek Consulting LLC); Erin Fox (University of Utah/ASHP); Terry Ocheltree (PharmTree); Sam Venugopal (PWC)

ISPE: Jean François Duliere, ISPE France Affiliate; Joseph Famulare (Genentech), ISPE International Board of Directors Liaison; Carol Winfield, ISPE Senior Director, Regulatory Operations; Thomas Zimmer, ISPE Vice President, European Operations