Validation of Clinical Trial–Related Systems in Smaller Enterprises

Existing risk-based approaches to computerized system compliance and validation as outlined in GAMP® 51 are applicable to a variety of life sciences organizations supporting or performing GxP-relevant activities. However, specific guidance on how to implement all the necessary measures and what to prioritize in small- and medium-sized enterprises is scarce.

The need for such guidance is significant. For example, there are approximately 26,000 medical technology companies in Europe, and 95% of them are small- or medium-sized companies, meaning each of these companies employs fewer than 250 persons and has an annual turnover not exceeding €50 million.2

Despite the importance of these companies to the pharma industry, the adoption or use of tailored validation approaches in small- and medi-um-sized enterprises is currently not addressed or described in any guidance or literature. As a result, small- and medium-sized enterprises continue to face the challenge of selecting and applying a suitable process for computerized system compliance and validation.3

The need for robust computerized system validation as the basis for the integrity, reliability, and robustness of data generated in clinical trials has recently been highlighted in the “Notice to Sponsors on Validation and Qualification of Computerised Systems Used in Clinical Trials” issued by the EMA in April 2020.4 This notice specifically states:

Failure to document and therefore demonstrate the validated state of a computerised system is likely to pose a risk to data integrity, reliability and robustness, which depending on the criticality of the affected data may result in a recommendation from the Good Clinical Practices (GCP) inspectors to the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) not to use the data within the context of an Marketing Authorization Application (MAA).

Therefore, small- and medium-sized enterprises supporting Good Clinical Practices-relevant activities by providing services and/or technology need to be ready to support their clients with documentation and evidence generated by a robust, reliable, but also right-sized quality management system (QMS).

Potential QMS Implementation Challenges

As Welsh and White have observed, “A small business is not a little big business.”5 In the pharma industry, this quote is especially true with regard to quality and validation. This becomes obvious in the resourcing of quality and IT departments. Whereas large organizations may have hundreds of people working on sometimes very specialized tasks and a dedicated sizable budget for quality and IT, small- and medium-sized enterprises often have less than a handful of experts, whose efforts may be limited by financial constraints. In the context of quality and validation, this may lead to issues around separa-tion of duties in some organizations.

At the same time, small- and medium-sized enterprises often provide a single or very few specialized services or software and therefore may not need the entire set of processes, checks, and balances that are often implemented and seen as “the standard” in larger organizations. Larger companies often must develop and maintain an extensive quality management system that covers all GxP areas to ensure appropriate standards are applied across the entire organization. It may start with high-level quality policies that are then detailed in underlying standard operating procedures (SOPs), work instructions, manuals, and other documentation for the various aspects and areas to be covered. In contrast, small- and medium-sized enterprises should be able to develop and maintain a much smaller quality management system that is focused on and tailored to the business and regulatory compliance aspects that are relevant to the services they provide. This quality management system may not require as many levels as a large enterprise’s quality management system.

ICH E6(R2), Guideline for Good Clinical Practice, 6 states that “the sponsor should implement a system to manage quality throughout all stages of the trial process.” Although “a sponsor may transfer any or all of the sponsor’s trial-related duties and functions to a Contract Research Organization (CRO),” the sponsor needs to ensure oversight of “trial-related duties and functions that are subcontracted to another party.” Furthermore, “the ultimate responsibility for the quality and integrity of the trial data always resides with the sponsor.”

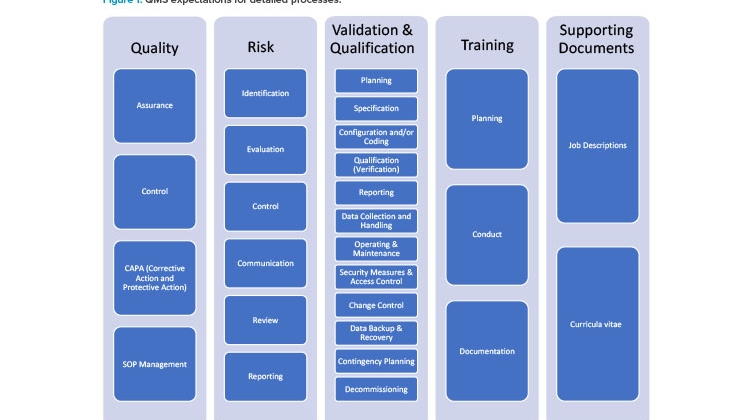

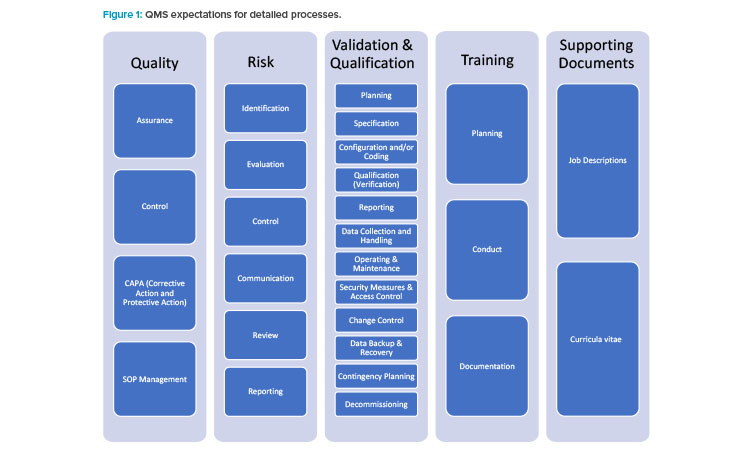

The 2020 EMA notice mentioned previously2 provides further clarification, stating “sponsors shall be able to provide the Good Clinical Practices inspectors of the EU/EEA authorities with access to the requested documentation regarding the qualification and validation of computerised systems irrespective of who performed these activities.” If a small- or medium-sized enterprise (or even a larger company) cannot support the sponsors by providing, for example, system requirement specifications or documentation and system access for Good Clinical Practices inspectors, “systems from such a vendor shall not be used in clinical trials.” 2 This is often interpreted to mean that service and technology providers need to implement a quality management system similar to that of sponsor organizations, which are often large pharma companies. Figure 1 illustrates the quality management system expectations for detailed processes.

At the same time, the quality approach should avoid unnecessary complexity, procedures, and data collection and follow the application of science- and risk-based methodologies. But how can one determine what is required? And how can enterprises implement the quality approach in an efficient, cost-effective, and justifiable way?

Quality

Among the biggest advantages of small- and medium-sized enterprises are the personalized management and flat hierarchies that make them agile and nimble in the market and allow them to address their clients’ needs quickly. This advantage should also be reflected in the enterprise’s basic quality approach.

This basic quality approach should ideally be documented in a single document that describes the following:

- The basic roles and responsibilities as they are required for the services provided: Even though auditors are very familiar with roles like “process owner” or “system owner” that are distinct from job titles, it may be more suitable in small organizations to use job titles and job descriptions to document the roles and responsibilities and reference those in the quality process descriptions. It should also be understood that the often-granular roles used by large organizations are not feasible for small- and medium-sized enterprises. The adequate separation of duties should be the guiding principle for the design of roles and responsibilities. Even though the GAMP® 5 Guide1 suggests a number of roles including, but not limited to, process owner, system owner, quality unit, corporate quality, operational quality, and subject matter experts, this does not mean that these roles cannot be com-bined and covered by very few individuals (in the extreme, by one individual covering process/system owner and subject matter expert and another individual covering all quality roles).

- The overall process for generating and maintaining the quality management system, including versioning and document control: Many companies use electronic document management systems to establish access control and versioning, but small companies can be compliant by maintaining a master standard operating procedures binder or storing the final documents in a protected area to which most employees are restricted to read-only access. Regardless of the approach chosen, the super-seded or retired processes need to be retained. The process for generating and maintaining the quality management system can be quite short and lean, focusing on:

- Steps to request a new process or update to an existing process

- Approval of processes before they become effective

- Communication and training of new or changed processes

- Maintenance and storage of all processes that ever became effective

- The internal and (if needed) external audit approach, planning, and documentation: This information can be recorded in a document or spreadsheet. Controls similar to those used for standard operating procedures need to be in place to prevent manipulation. This is especially important if the small- or medium-sized enter-prise outsources some aspects of the provided services (e.g., to cloud service providers).

- An approach for continuous improvement and corrective/preventive actions: This information may also be stored in a document or spreadsheet; however, most technology providers have systems in place for service desk activities. This system can potentially be configured to support corrective action and protective action (CAPA) activities as well. The overall number of incidents and corrective action and protective actions should drive the approach to management review and key performance indicators (KPIs). Smaller companies may not have a need to implement detailed processes for this if there are only few corrective action and protective actions and every corrective action and protective action is discussed within the entire management team. Whichever methodology is used should be documented as such in the process description.

Risk Management

Risk management activities are fundamental to all attempts to build an efficient, cost-effective, and defensible quality management system and validation framework. Protecting patient safety, data integrity, and regulatory compliance needs to be at the heart of all risk evaluations.

A similar approach to the one outlined previously for the continuous improvement and corrective/preventive actions may be utilized for risk assessment and management. Risk may be assessed and managed for each individual project or product; however, an extensive approach to aggregate the risks and have them reviewed by management may not be necessary in small organizations.

Key questions to be addressed in risk assessment activities are:

- What parts of the provided services can directly or indirectly impact patient safety or data integrity?

- Do the services contribute to or directly perform drug safety activities (e.g., collection or processing of serious adverse events)?

- Do the services contribute to the collection or processing of clinical trial data that support a clinical end point?

- Do the services contribute to the storage or distribution of investigational products?

- Do the services contribute to the protection of patient rights (e.g., informed consent)?

- What parts of the provided services contribute to a regulatory submission?

The detailed answers to questions such as those outlined here allow the small- or medium-sized enterprise to focus on critical areas in all aspects of quality. It is critically important that experts in the organization have in-depth knowledge of the process and the system and a robust understanding of the regulatory framework and data integrity expectations. This knowledge enables the risk management activities to find and document the appropriate validation approach. Also, it is important to carefully align the risk assessment with the needs of clients. Understanding how the customer intendeds to use the product or service is important for the small- or medium-sized enterprise’s risk evaluation. The risk mitigation activities may be included in quality agreements or service-level agreements.

For example, an electronic data capture (EDC) provider will significantly contribute to the collection and processing of clinical trial data that support a clinical end point. Depending on the trial design and the data to be collected, system downtimes of one or even more days may be acceptable. However, if the electronic data capture system is also used by the customer to collect serious adverse events that need to be processed and reported within tight regulatory timelines, such downtimes may not be acceptable.

Small- and medium-sized enterprises may need to invest significant resources in risk management activities because they are crucial for reducing effort in a justified and compliant manner. The risk management methodology itself should be scaled for purpose; for example, it may not be necessary to document risks and corresponding mitigation actions or acceptance for every individual user requirement associated with a computerized system. In-stead, a clear, structured, and detailed description of the intended use, the associated system functions, relevant procedural and technical controls, and the associated risks may be sufficient in a number of cases.

Validation

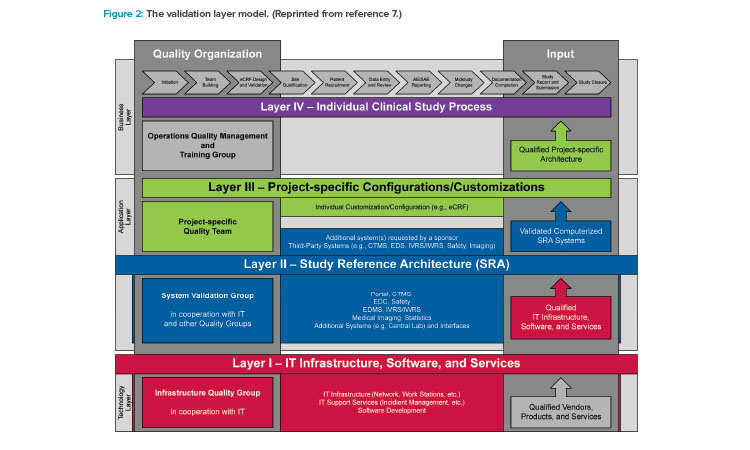

The validation of Good Clinical Practices systems and data has been described in the GAMP® Good Practice Guide: Validation and Compliance of Computerized Good Clinical Practices Systems and Data.7 In particular, the guide’s validation layer model (Figure 2) and the risk assessment and validation guidance for tools that support Good Clinical Practices processes support a lean, efficient validation approach for small- and medium-sized enterprises.

Layer I

Layer I (qualified IT infrastructure, software, and services) establishes the foundation for the validation of computerized systems. The small- or medium-sized enterprise needs to establish a lean set of processes that focuses on qualification of the relevant IT infrastructure, security and data protection, software development, and IT support services.

Qualification of the relevant IT infrastructure

Qualification of the IT infrastructure may include:

- Servers for relevant software and data storage: Qualification can be achieved by a set of templates that capture the relevant data for hardware and the steps required to install operating systems and other software components (e.g., drivers, viewers, frameworks).

- Systems that support the core business but do not hold or process clinical data: Examples include help desk systems, incident management systems, and office applications. Capturing the installation and configuration details as well as the version(s) and release dates of the installed system is critical.

Generally, the need for IT infrastructure qualification is higher if the small- or medium-sized enterprise directly hosts systems that process or store regu-lated data. Enterprises that develop software that is implemented and operated on the customer’s premises may not need to qualify all of their infrastructure. In such organizations, the qualification activities should focus on systems that directly support software development and testing of regulated software or important support services (e.g., a support hotline).

Security and data protection

The following aspects of security and data protection need to be considered:

- Patch management (operating system, browser, applications)

- Classification of data (e.g., sensitive, confidential, public, personal identifiable information)

- Physical and logical security (e.g., virus protection, hardening of systems, intrusion detection)

Obviously, some of these items (e.g., virus protection) are essential to protect the core business of the small- or medium-sized enterprise as well as the client. The relevance of other items may depend on the type of services offered. For example, a software as a service (SaaS) provider typically needs to have an intrusion detection system and process in place, whereas a software provider whose software is installed and operated on the client’s premises often does not require this.

Software development

At minimum, software development validation concerns include:

- Specification

- Development and testing

- Deployment and release

For small- and medium-sized enterprises that develop software, this is an area of critical (quality) activities. First, validation is required to ensure that the software is working as designed and has no critical bugs. Second, documentation is essential to enable teams to organize their work during development. Third, a robust approach to software development and documentation enables the small- or medium-sized enterprise’s customers to build on that documentation and limit their validation efforts to verifying that the system is fit for the intended use and supports the business process, rather than verifying that all required individual functionalities are working as designed. For this reason, a robust software development approach and documentation can be a market differentiator for the vendor.

Table 1 describes the most important aspects to keep under control. These aspects need to be covered regardless of the development methodology and organizational setup (waterfall, agile, DevOps, etc.). Small- and medium-sized enterprises should try to build a robust end-to-end solution that is suitably integrated to allow team members to answer the key questions. A strong, documented connection between requirements and testing is espe-cially important. To achieve this, the quality requirements and aspects should be considered—along with programing, development, and business needs—when a software development platform is selected and implemented.

IT support services

Generally, the following scenarios are relevant to layer I validation:

- Service/help desk

- Incident management

- Disaster recovery/business continuity

| Aspect | Key Questions to Address |

|---|---|

| Requirements management | Which requirement was implemented/released in which version? |

| Version management | Which versions of the software are in development, released, and in use with support? |

| Test management | How and when was the functionality tested? How can this be traced back to the requirements? |

| Release management | When was a version of the software released/ implemented? |

| Bug fi xing | How and when have bugs been fi xed? How is bug fixing integrated into the overall development and release processes? |

These are very important concerns if the technology provider offers software products in infrastructure as a service (IaaS), platform as a service (PaaS), or SaaS. This type of offering often requires significant investments in hardware, software, services, processes, and people to establish:

- Service/help desk coverage

- Backup and restore services

- Incident management process and Incident tracking

- Disaster recovery sites, plans, and exercises

- Business continuity plans and exercises

For small- and medium-sized enterprises, it may be more cost-effective to outsource some of these activities to specialized third parties such as cloud service providers. However, the adequacy of these specialized third parties needs to be verified via qualification activities such as audits or questionnaires.

Layer II

Layer II (study reference architecture) of the validation layer model addresses the validation of computerized systems that support the processes to conduct a clinical trial. Small- and medium-sized enterprises that offer services to support clinical trials need to establish a lean set of processes focused on implementing compliant systems that outline the generation of the required documentation and evidence and can also be easily adapted to each customer’s requirements. Customers often expect that the small- or medium-sized enterprise will follow the customer’s processes in the implementation and integration effort.

Generally, the following scenarios are of concern:

- Systems that support clinical trials directly or as a central, cross-study application: For example, clinical trial management systems (CTMS) that manage all trials in a central database often require significant validation efforts during their implementation because configuration/customization and testing activities on a study-by-study basis are not done or are very limited. An analysis of the supported business process that considers business intent, pa-tient safety, and data integrity will reveal the critical steps, actions, and data. This analysis needs to be the nucleus of the risk-based validation fo-cused on the identified critical aspects. Small- and medium-sized enterprises that provide such technology solutions should have robust software development documentation that allows the elimination of functional testing on the customer side in this phase. The validation should focus on verifying that the configuration of the system is supporting the business process of the customer as expected.

- Systems that provide a platform and need to be significantly configured/customized to support individual clinical trials (e.g., electronic data capture systems): Typically, such systems require a very limited validation approach focused on functionalities used across all clinical trials, and a significant risk (as outlined previously) is associated with these systems. In an electronic data capture system, the functionality could be the general query functionality. See layer III for more details.

Layer III

The validated systems and platforms are then configured or customized in layer III to build the trial-specific solutions required. The small- and medium-sized enterprise needs to establish a lean set of processes that focus on efficiently building these solutions, often based on customer requirements, in a compliant way.

Generally, the following scenarios are of concern:

- Configuration of systems for specific trials: As outlined previously, the configuration efforts may vary greatly depending on the type of system and/or the complexity of the study. Whereas a clinical trial management systems system may simply require a setup of the study through the user interface, an activity that, of course, does not require validation, the setup of an electronic data capture system is significantly more complex and requires programming-like skills. Additionally, data collect-ed via the electronic data capture systems are often directly related to the safety of the participants and the end points of the clinical trial. Most of the validation activities need to be performed on a study-by-study basis to ensure the trial-specific needs—such as electronic case report form (eCRF) design and edit checks—are met. An analysis of the study processes and study protocol focused on patient safety and data integrity is required. Generally, it is advisa-ble to organize such validations to enable a potential reuse of validated elements, if possible. For example, electronic case report forms capturing demographic data tend to be very similar across studies, so it may be possible to reuse an existing, already validated electronic case report form. Small- and medium-sized enterprises that provide services to set up technology solutions for individual clinical trials should focus on identifying the critical data points for the study and ensuring thorough testing of configured functionalities that capture and/or process these data.

- Development of interfaces, reports, or data analysis programs based on existing platforms (e.g., business intelligence solutions or specialized development platforms): These items usually require fewer validation efforts because they are based on qualified standard platforms. However, depending on the data that are processed or reported and the potential decisions that are made based on these data, a robust and significant validation effort may be required. For example, interfaces and reports for electronic data capture or safety data are often critical in nature and should be validated. Small- and medium-sized enterprises should achieve an in-depth understanding of the data, data flows, and data usages. This will enable the enterprise to focus the validation effort to the data elements that matter most.

- Building secure and robust data exchange platforms with clients and third parties: Data integrity can also be at risk when data are transmitted between multiple parties. Based on agreements reached between these parties, a secure platform should be established to exchange data. Any re-quired validation activities must focus on access control and security. Small- and medium-sized enterprises that offer such platforms as technology solutions need to focus their effort in these areas.

Layer IV

Layer IV (individual clinical study process) emphasizes that validated systems must be used according to the applicable business processes for the execution of the clinical trial. The high-level processes are usually applicable for all clinical trials; however, the details may differ greatly from one trial to another as study protocols differ with regard to indication, trial design, end points, target populations, and inclusion criteria. Established systems and plat-forms continue to evolve and improve, but new technologies may be needed to meet individual trial requirements.

The relationship between the business process and the supporting technology is often ignored or underestimated in its importance. Small- and medium-sized enterprises should proactively reach out to clients and gain a robust understanding of their business processes. The better the processes are understood, the better they can be supported by an agile and nimble small- or medium-sized enterprise.

Training

Training has the following objectives:

- Staff are aware of the relevant processes and can follow them.

- Required competencies and skills are developed for the completion of tasks.

The second objective may be achieved via external training or through hiring already fully qualified personnel, but the first objective always requires an internal training program.

All training must be planned for the relevant roles, and the applicable syllabus/training plans should be documented. The training assignments for processes should be in line with the scope or audience descriptions in the process documentation. Also, after training has taken place, documentation must be completed and filed. To demonstrate compliance, organizations should be able to show:

- Training transcripts for individuals (e.g., individual training logs)

- Who has completed specific training (e.g., attendance lists for training sessions)

| Aspect | Larger Enterprises | Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises |

|---|---|---|

| QMS | Extensive quality management system is required to cover all multiple GxP areas and a wide range of services and activities. The quality management system is often implemented as a multilayer document hierarchy with complex relationships and references. |

quality management system focuses on the services and activities performed. It may be single-layered with a limited number of standard operating procedures focused on the business at hand (e.g., software development, system operation). Stakeholder reviews are shortened or eliminated. A master standard operating procedure binder may be maintained, or final documents may be stored in a protected area to which most employees have read-only access.

|

| Management review | Management review is often described in an standard operating procedure with details on frequency, participants, data to be reviewed, and documentation requirements |

Management review can be informal in small companies with few employees/managers; it requires appropriate documentation such as meeting minutes. |

| Roles and responsibilities | Problems with the segregation of duties are seldom encountered. Teams are often large, with very detailed division of responsibilities. | Maintaining the segregation of duties may be challenging because teams/departments may be very small. Segregation may be achieved by combining roles and responsibilities and very careful planning of resources and/or by outsourcing of certain tasks. |

| Job descriptions | Descriptions are often for very specialized roles but without details for specific products. These details are often included in project documentation. | Descriptions could be very detailed and eliminate the need for further specification in project documentation. However, roles may be combined (e.g., the software developer may also have support responsibilities). |

| Risk management | Risk management is often implemented hierarchically (e.g., moving from team/project risks to department risks, regional risks, and global risks). | A documented risk assessment and management approach on the team/project level may be sufficient. |

| Critical thinking | Critical thinking needs to be continuously promoted and reinforced as employees of large companies may tend to just follow the rules. | Critical thinking is more predominant in smaller enterprises because every employee is more directly contributing to the success (or lack of success) of the company. |

| Tools | Extensive tool sets that are interfaced and provide quality metrics are often used. Typically, larger enterprises can afford “best of breed” system implementations. | It is recommended that smaller enterprises carefully select tools that support the business purpose as well as the quality aspects. Quality aspects should be part of the requirements (e.g., in software development tools). However, clever usage of functionalities provided by office software utilizing automated exports of relevant data out of the business tool set can establish robust quality documentation. |

| Project management | Large teams, which may be distributed globally, often require extensive planning and management. Typically, teams follow the quality management system strictly. |

Smaller teams are often self-managed and use agile approaches. Unless they are well trained, these teams may value working services and products over quality documentation. |

| Change control | Change control needs to focus on the implemented changes to the computerized system (infrastructure, software and configuration, processes, training). |

Change control needs to focus on version control and release of the software, including its validation/qualification documentation. |

| Documentation approach | Documentation is mostly electronic, in databases or electronic document management systems. |

Documentation can be paper based or electronic. The paper-based approach may be more cost efficient when teams are small and in a single location. |

Organizations need to able to demonstrate that all staff have been trained in time for the roles they are to perform. This sounds simple, but the details can be quite challenging as circumstances change. For example:

- Staff may change roles or take on new responsibilities.

- Staff need to be retrained as processes evolve.

- Enterprises define new roles that require new training plans.

Very small enterprises may be able to manage training documentation with spreadsheets, but growing organizations may need a system to track trainings and processes. This system should describe:

- Training plan creation, review, and maintenance

- Assignment of training to individuals and control of timely training completion

- Documentation of training

- Training of new hires (“onboarding”)

Whereas larger organizations may aim to become paperless in training documentation, small- and medium-sized enterprises may find it more cost effective to maintain paper records. Especially if the entire organization is in one location, generating paper records like sign-in sheets is easy and efficient.

Supporting Documents

The creation and maintenance of curricula vitae (CVs) and job descriptions is important to support training as well as various human resources and business development activities.

From a quality and compliance perspective, an accurate curricula vitae is evidence of staff qualification to perform a regulated activity. Additionally, clients typically request curricula vitaes of important staff working on their projects.

Job descriptions help identify the right resource for a specific role or position. Job descriptions should include an explanation of the responsibilities and tasks, the minimum qualifications, required levels of education and experience, and the organizational details. The curricula vitae of the person performing a role should demonstrate that they meet the job description requirements, or a justification for the assigned individual should be documented. If the justification entails improving the competencies and skills of the assigned individual through training, a detailed training plan with timelines should be included.

Conclusion

The regulatory expectations for computerized system validation do not differentiate between larger and smaller organizations. All organizations that support GxP-relevant processes have a responsibility to protect patient safety and data integrity. However, small- and medium-sized enterprises often have the advantage of flat hierarchies and personalized management, and the specialized services that these enterprises provide should be considered in the design and evaluation of their quality management system.

Small- and medium-sized enterprises often have the advantage of flat hierarchies and personalized management.

Small- and medium-sized enterprises need to have a clear understanding of the services they provide, the GxP-relevance of these services, and the applicable regulatory framework. This knowledge is essential for risk assessments focusing on data integrity and patient safety, the determination of ap-propriate controls and validation approaches, and the creation of proper documentation that can be used in audits and inspections. There is no regula-tory expectation that small- and medium-sized enterprises implement expensive tools and systems for quality-related tasks, but all enterprises must follow validated processes and have adequate documentation to prove that the necessary controls are in place. In many cases, standard office software suites and/or trustworthy and reasonably priced cloud services can establish a robust quality management system, if they are used correctly and embedded in the relevant processes. We cannot overstate the importance of risk assessment that is based on critical thinking, focuses on the business purpose, considers the organizational structure, and leads to effective controls.

Table 2 compares typical validation and quality approaches for larger and smaller enterprises but does not offer one-size-fits-all recommendations. Every organization needs to determine the appropriate approach by considering the nature or their services and products, the size and structure of their organization, the existing infrastructure and tool sets, and other factors. In some areas, potential customers will expect vendors to have quality management system certification (e.g., ISO 9001). Such certification may require the enterprise to implement additional activities and controls.

There is a clear regulatory expectation that the sponsor can make evidence supporting validation available to inspectors. Given this expectation, the enterprise providing services may need to hand over copies of key validation documents to the sponsor during the initial system implementation or during later updates/upgrades. Depending on the nature of the outsourced services, robust contractual agreements with well-defined roles and responsibilities, a robust supplier assessment, and a quality agreement may suffice to establish regulatory compliance. However, if significant parts of the system implementation and validation are executed by the supplier, the contracts and quality agreements should include aspects of inspection support as required to provide additional supplier-generated documentation or explanation of the supplier’s quality management system that generated evidence and documents. Sponsors may not get approval of marketing authorization applications if the supporting data originate from a system that has not been adequately validated; therefore, a robust quality management system that generates reliable validation evidence must be considered business critical.