For example, not everyone regards, a priori, the relative damage to our land, water, or air in the same way. Others can emphasize individual burdens due to local (regional setting) factors, such as water use in dry regions, or to the particular type of products, such as organic solvents in oligonucleotide production. Such ranking can also be due to special interest goals influenced by customers, regulations, or bylaws.

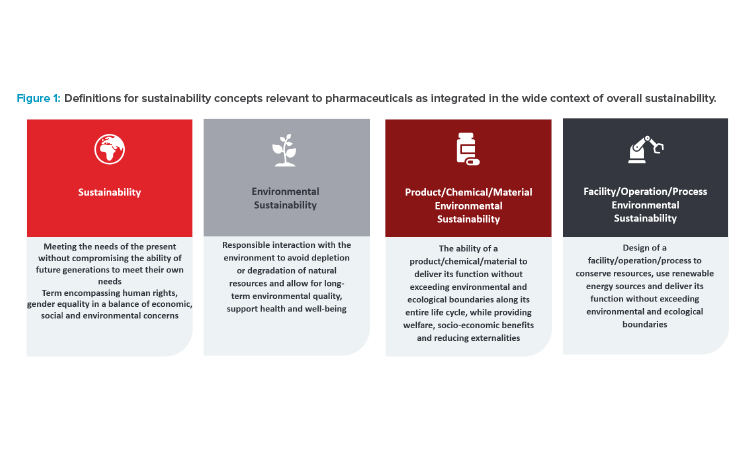

The general UN definition of sustainability—“meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”—is also the basis of approaches used in pharmaceutical applications.

Consistent with the preceding general considerations, environmental sustainability in the pharmaceutical industry can be perceived from two directions: from the side of the product or operations, processes and/or facilities, both of which are required to achieve a comprehensive sustainability program. Sustainability of pharmaceutical products can be defined considering the recent JRC Technical Report (2022), which has provided the following definitions for sustainable chemicals and materials:

“Sustainability could be formulated as the ability of a chemical/material to deliver its function without exceeding environmental and ecological boundaries along its entire life cycle, while providing welfare, socio-economic benefits and reducing externalities. Overall sustainability should be ensured by minimizing the environmental footprint of chemicals on climate change, resource use, ecosystems and biodiversity from a life cycle perspective.”

This definition is based on criteria from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2004) involving reducing the consumption of resources and energy and avoiding the use of dangerous substances. Additional principles refer to the following:

- Use of harmless substances or, where this is impossible, substances involving a low risk for humans and the environment, and manufacturing of products in a resource-saving manner.

- Reduction of the consumption of natural resources, which should be renewable wherever possible, and avoidance or minimization of emission and introduction of chemicals or pollutants into the environment.

- Avoidance, already at the stage of development and prior to marketing, of materials that endanger the environment and human health during their life cycle and make excessive use of the environment as a source or sink.

Sustainability in Application

The preceding sustainability criteria can also be applied to facilities, operations, and processes, prompting design that conserves natural resources, such as energy and water, and utilization of renewable energy sources within the ecological boundaries. Sustainable process or facility design requires a new way of thinking and approaches to a project: be it a new build, renovation, or operations development and maintenance.

This now includes employing critical thinking and a science-based approach to innovations and solutions. More specifically, this involves such design factors as the site, surrounding environment and community, the buildings (existing or proposed), their interiors, operations, and any ongoing maintenance processes, until the project reaches the end of its life and its parts are recycled or reused. This approach encourages an early engagement and harmonization of all stakeholders, including designers and building users in the building/process owner’s purview, while establishing formalized project needs and performance targets.

Finally, the approach taken to facilities and their operation should form part of a wider program of attaining holistic sustainability goals that span across the value chain: all business operations (R&D, manufacturing and supply logistics, sales and marketing), the role of various tiers of suppliers of goods and services in the supply chain, and the end-to-end impact of medicines on the environment (covering both used and unused medicines).

The various program elements within the framework presented in Figure 1 will need collective reporting that is accurate and auditable to ensure there is no suggestion of greenwashing. Some of the many themes relevant to the general concept of sustainability will be developed elsewhere in this issue of Pharmaceutical Engineering®.